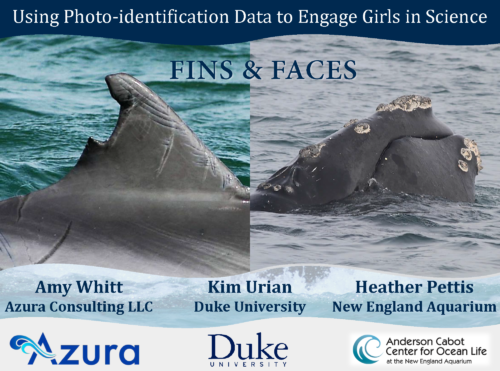

Fins & Faces: Using Photo-identification to Study Dolphins & Whales

Over 1,700 scientists, managers, policy makers, and students attended the 22nd Biennial Society for Marine Mammalogy Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals during October 22-27, 2017, at the Halifax Convention Centre in Nova Scotia, Canada.

A common theme throughout the conference was the conservation and heightened awareness of the many marine mammal species that face extinction within the next few years and decades. Our spirits were lifted a bit with the success story of the recovering Mediterranean monk seal populations. However, the current, disastrous threats to some species, like the vaquita porpoise and the North Atlantic right whale, overshadow this one success story, adding to our growing anxiety and uneasiness about what may happen to these species under our watch.

The recovery of these species requires immediate actions which rely on effective communication of science to all stakeholders and decision makers. Not only do we hope to engage the people who can support and ensure direct conservation actions, we also strive to foster an excitement for marine mammal science to promote the next generation of marine scientists.

On behalf of coauthors Kim Urian (Duke University) and Heather Pettis (New England Aquarium), Amy Whitt (Azura) presented “Fins & Faces: Using Photo-identification Data to Engage Girls in Science”. During this oral presentation, Amy described how Azura has used marine mammal research to engage girls in science via the Eureka! Program. Girls were the target of this engagement because women are still poorly represented in the sciences, particularly in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) careers. Poor female representation is attributed to several issues, particularly the “leaky pipeline”, the attrition of women as they move up the ranks. These pipeline leaks are caused by numerous challenges, such as the increased work-life balance, sexual harassment/discrimination, lack of financial/childcare support, and implicit bias, that women experience both in the field and in office environments. With all of these challenges and more, why do women stay in this field? Because we are hooked on the science! That was our motivation for getting involved in the Eureka! Program…to get girls hooked on marine mammal science.

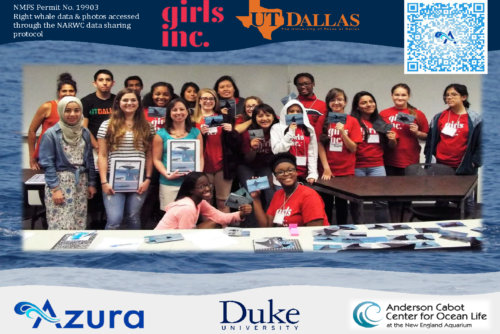

The Eureka! Program is a summer camp designed to introduce girls to different science careers and to motivate them to pursue post-secondary education and careers in STEM fields. In partnership with Girls Inc. Metropolitan of Dallas and the University of Texas at Dallas, we targeted middle school girls from socioeconomically challenged families in the Dallas, Texas area.

We introduced the girls to marine mammal science and a technique that marine mammal scientists use to study the distribution, movement patterns, abundance, and social interactions of whales and dolphins. Photo-identification is the process of using photographs of natural markings to distinguish one individual animal from another. Just like we have different hair styles, skin tones, freckle patterns, and other physical features that distinguish us from one another, many species of whales and dolphins have physical characteristics that are unique to individuals. For example, North Atlantic right whales have distinct patterns of callosities (raised tissue) on the tops of their heads that are unique to individuals, and bottlenose dolphins have different nicks and notches along the trailing edges of their dorsal fins. During our photo-identification activities, the girls got to analyze actual photographic data of these species.

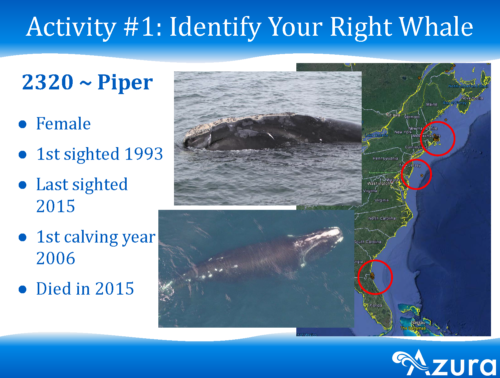

Activity #1: Identify Your Right Whale

We developed a miniature catalog from New England Aquarium’s full right whale catalog of 723 whales. Our mini catalog included 24 right whales, and a mix of males and females of different age classes. Each girl was given an “unknown” right whale photo to match to the mini catalog. We had 6 copies of the mini catalog, so we split the 20 girls into groups of 6. They had to verify their matches with others in their group. They matched the whales based on callosity patterns; white scars, blow holes, fluke tips; divots in their backs; and dip/depressions in the rostrum (seen in profile).

Once a girl identified her whale, we verified its identity and checked the Right Whale Summary Sheet in our mini catalog to learn more about her whale (age, sex, known parents, etc.). She also mapped sightings of her whale using Google Earth and, we compared movement patterns and distributions of the different whales. For example, the female right whale “Piper” was first sighted in 1993 and had her first calf in 2006. She was often sighted up and down the U.S. east coast between the feeding grounds off New England and the calving grounds off Florida and Georgia until she passed away in 2015. We used Piper and other deceased right whales as an opportunity to discuss the main causes of right whale population decline: entanglement in fishing gear and ship strikes.

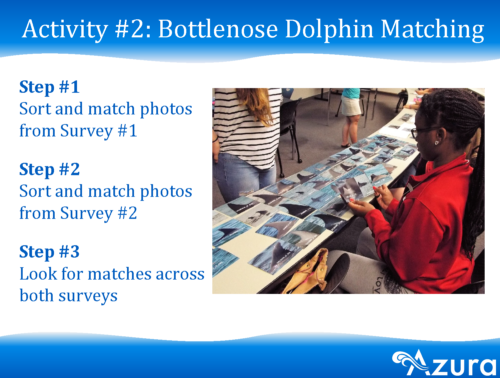

Activity #2: Bottlenose Dolphin Matching

Using photographic data provided by Duke University and collected from two surveys on bottlenose dolphins off the coast of North Carolina, the girls sorted and matched images of dorsal fins from each survey and then looked for matches across the two surveys. They first weeded out the “clean” fins that did not have distinguishing marks and then looked for nicks, notches, and tears but not scrapes or scratches which can heal over time.

After making their matches within and across the surveys, the girls got to use a bit of math to calculate the size of their population of North Carolina dolphins. This mark-recapture method uses the number of identified (marked) dolphins during the 1st survey, the number of dolphins identified during the 2nd (recapture) survey, and the number of dolphins matched between the two surveys. By using this mark-recapture method, researchers can assess the abundance of a population over a period of time to see if the population is decreasing or increasing.

Amy concluded the presentation with a summary of ways in which scientists can contribute to public outreach and education. From working with schools, teachers, other researchers to develop activities for different age groups to serving as a mentor/role model for young women aspiring to be scientists, there are many ways that we can get kids hooked on marine mammal science and help them understand that their career potential is not limited by their economic status, physical location, or gender.